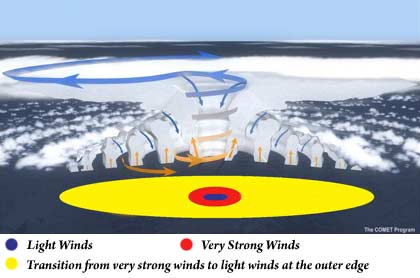

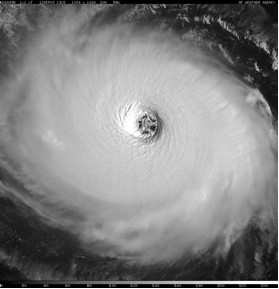

Hurricane Structure A mature hurricane is nearly circular in shape. The winds of a hurricane are very light in the center of the storm (blue circle in the image below) but increase rapidly to a maximum 10-50 km (6-31 miles) from the center (red) and then fall off slowly toward the outer extent of the storm (yellow).

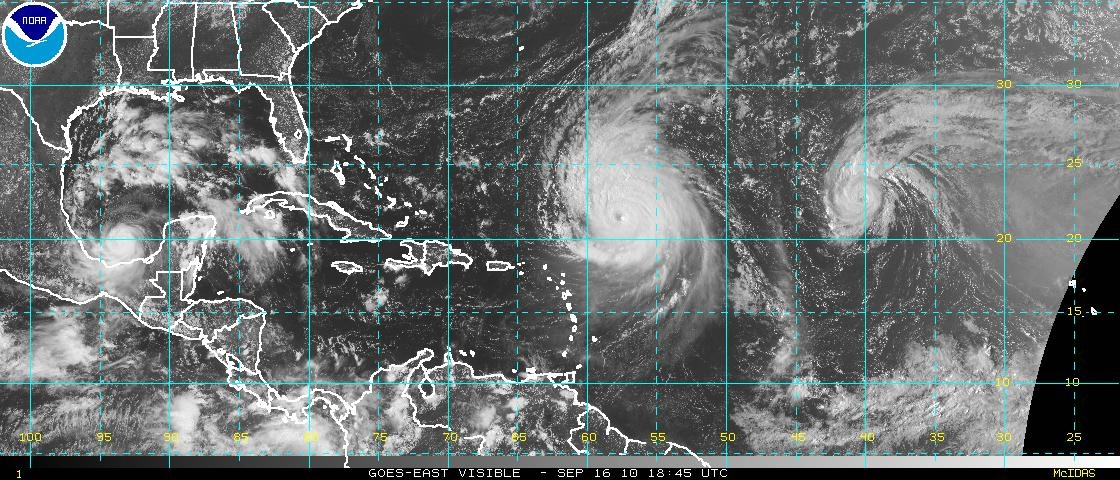

The size of a hurricane’s wind field is usually a few hundred miles across, although the size of the hurricane-force wind field (with wind speed > 117.5 km/h [73 mph]) is typically much smaller, averaging about 161 km (100 miles) across. The area over which tropical storm-force winds occur is greater, ranging as far out as almost 500km (300 miles) from the eye of a large hurricane. One of the largest tropical cyclones ever measured was Typhoon Tip (Northwest Pacific Ocean, October 12, 1979), which at one point had a diameter of about 2100 km (~1350 miles). One of the smallest tropical cyclones ever measured was Cyclone Tracy (Darwin, Australia, December 24, 1974), which had a wind field of only 60 miles (~ 100 km) across at landfall.

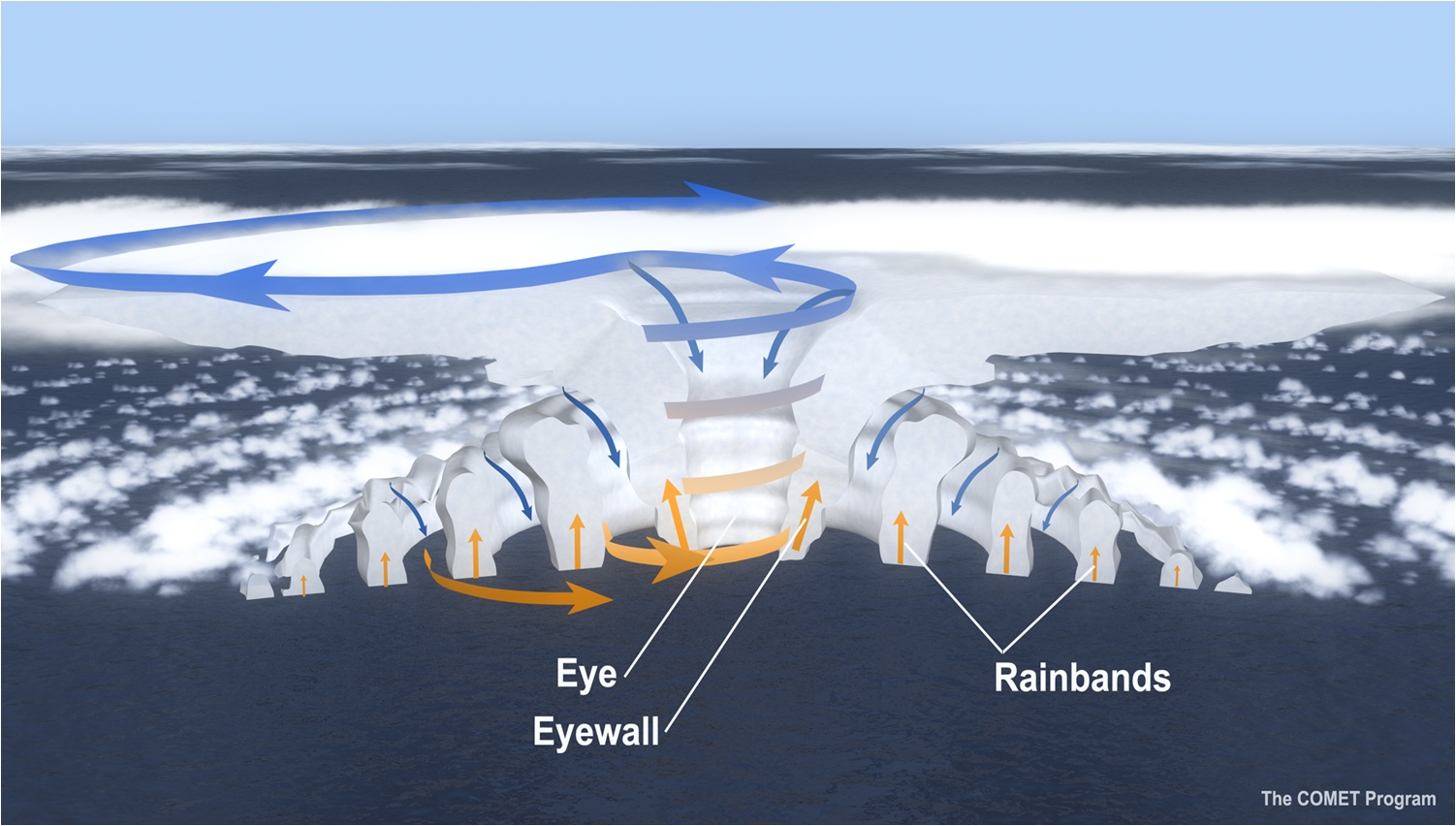

A mature hurricane can be broken down into three main parts: the eye, eyewall, and outer region.

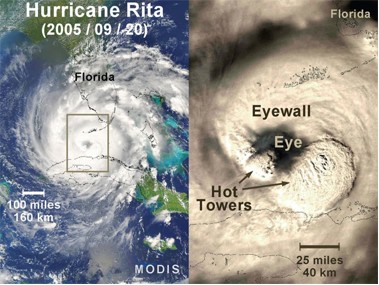

In mature hurricanes, strong surface winds move inward towards the center of the storm and encircle a column of relatively calm air. This nearly cloud-free area of light winds is called the eye of a hurricane and is generally 20-50 km (12-30 miles) in diameter. From the ground, looking up through the eye, skies may be so clear that you might see the stars at night or the sun during the day. Surrounding the eye is a violent, stormy eyewall, formed as inward-moving, warm air turns upward into the storm (see Hurricane Development: From Birth to Maturity). Usually, the strongest winds and heaviest precipitation are found in this area.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the most destructive section of the storm is usually in the eyewall area to the right of the eye, known as the right-front quadrant. Based on the direction of movement of a hurricane during landfall, this section of the storm tends to have higher winds, seas, and storm surge.

Outside the eyewall of a hurricane, rainbands spiral inwards towards the eyewall. These rain bands are capable of producing heavy rain and wind (and occasionally tornadoes). Sometimes, there are gaps between the bands where no rain is found. In fact, if one were to travel from the outer edge of a hurricane to its center, one would typically experience a progression from light rain to no rain back to slightly more intense rain many times with each period of rainfall being more intense and lasting longer until reaching the eye.

An In-Depth Look at Hurricane Eyes and Eyewalls

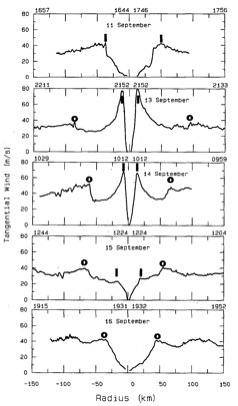

Not all hurricane eyewalls look the same, and the size and shape of a particular hurricane’s eyewall often changes during the hurricane’s lifetime. In what may be considered a “typical” hurricane, a single eyewall surrounds a nearly circular eye that is mostly cloud-free. However, eyewalls of strong, long-lived hurricanes sometimes contract over time, during which the maximum wind speed in the hurricane typically increases. Then, a new eyewall may begin to form outside of the original contracting eyewall, often from one of the innermost spiral bands. When a hurricane has more than one eyewall at once, it is said to have concentric eyewalls. After the outer eyewall forms, the inner (original) eyewall may decay, during which the maximum wind speed in the hurricane typically decreases. Eventually, the outer eyewall may become the only one left. The new outer eyewall may then begin to contract, leading to another period of hurricane strengthening. This cycle, which may repeat multiple times, is called an eyewall replacement cycle.

Eyewall replacement cycles can have very serious consequences, especially when they occur just before landfall. At great cost to life and property, Hurricane Andrew (1992) unexpectedly strengthened to a Category 5 hurricane while making landfall in southeastern Florida immediately following an eyewall replacement cycle. In addition to large and rapid intensity swings, eyewall replacement cycles usually cause hurricanes to grow larger. This occurred as Hurricane Katrina moved through the Gulf of Mexico, resulting in a much larger and more dangerous storm threatening New Orleans. During landfall, larger hurricanes do more wind damage, but they are also accompanied by greater storm surge and wave heights due to increased wind fetch. When multiple eyewall replacement cycles occur, the hurricane can continue to grow larger with each cycle. Hurricane Igor (2010) went through multiple cycles and became one of the larger Atlantic hurricanes on record, causing significant waves and rip currents along the U.S. east coast, even while staying far out to sea. Hurricane eyes are not always circular. Oblong, elliptical eyes are sometimes observed, especially in weaker hurricanes. A strong hurricane may have a polygonal eyewall, where the eye takes the shape of a triangle, square, pentagon, or hexagon. Polygonal eyewalls are often associated with eyewall mesovortices, which are smaller-scale atmospheric swirls that can form within the eye and which can produce extremely strong winds. Eyewall mesovortices may remain nearly stationary relative to the hurricane’s center, or they may rotate around the center within the eye or even pass through the hurricane’s center.

|