Introduction

Hurricane Irma was the first cyclone of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season to reach category 5 intensity. This intensity was held for a record-breaking 13 days from August 30 to September 12, 2017. It was the first of the two costliest hurricanes on record to hit the Caribbean, the second being Hurricane Maria LINK two weeks later. It was among the strongest major hurricanes to make landfall in the U.S. during the extremely active 2017 season, hitting the Florida Keys as a category 3 hurricane on September 10th, two weeks after Hurricane Harvey hit Houston. Evacuation orders were issued for more than six million people in FL alone, yet 134 fatalities still occurred in association with this storm. Irma is known for the far-reaching and catastrophic damage it caused to homes, infrastructure, and wildlife in the Caribbean, rendering the island of Barbuda nearly uninhabitable.

Meteorology and Forecasting

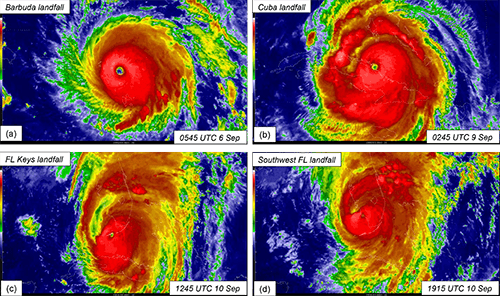

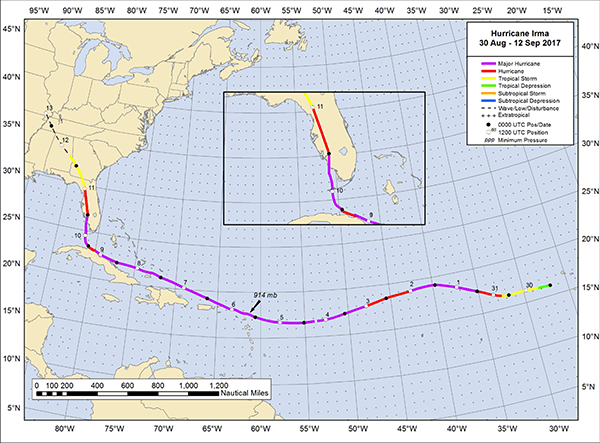

Description: On August 27th, 2017, a tropical atmospheric wave was produced off the west coast of Africa, producing deep convection (warm air rising far into the atmosphere) concentrated in the northern portion of the wave over the next couple of days. By August 30th, circulation was well-defined in satellite images, indicating that it had become a tropical depression. Six hours later, the depression became a tropical storm. After moving westward, it encountered a mid-level ridge (high pressure system) to the north, and rapidly intensified due to low wind shear, moist atmosphere conditions, and somewhat warm sea surface temperatures (SST). It became a hurricane on August 31st, 30 hours after becoming a tropical depression. It reached major hurricane status on September 1st, only two days after genesis; this rapid intensification over a two-day period was remarkable and not well predicted. It fluctuated in intensity for a few days before turning west-northwestward on September 4th due to the high-pressure system to the north. The turn positioned it over higher sea surface temperature waters, which helped it to intensify over the next couple days. It reached maximum intensity on September 5, making landfall on Barbuda in the early morning the next day as a category 5 hurricane. It fell on St. Martin later that morning, and the British Virgin Islands in the late afternoon.

Over the next two days, Hurricane Irma weakened slightly and tracked north of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. On September 8th, it made landfall in the Bahamas as a category 4 hurricane, ending a 60-hour period of category 5 intensity (the second longest such period on record behind the 1932 Hurricane of Santa Cruz del Sur, Cuba). After turning towards Cuba, Irma once again strengthened and made landfall as a category 5 storm on September 9th - the most intense storm to hit Cuba since 1932. As it tracked along the Cuban Keys, its strength fluctuated as it began to track northwest towards Florida. It made landfall near Key West, FL as a category 4 storm on September 10, after which it weakened to a category 3 when it experienced strong wind shear over land. By early morning of September 11, the storm had weakened to a category 2. By noon the same day, it had become a tropical storm near Gainesville, FL. It continued to weaken over northern Florida and Georgia, and fully dissipated over Missouri by September 13th.

Intensity: Category 5 (Saffir-Simpson Scale)

Damage

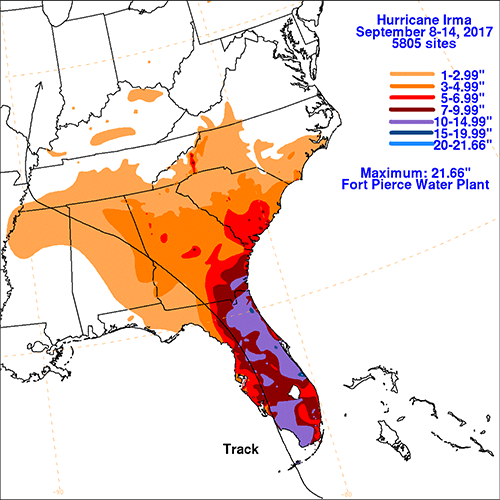

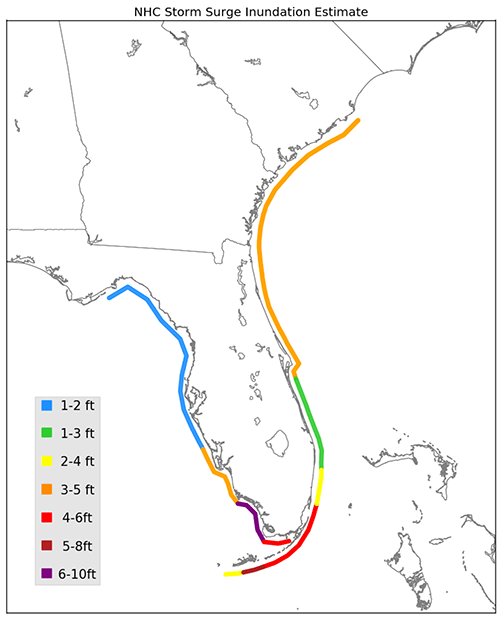

Storm tide:

Cost:

Adaptation (What was learned)

The destruction caused by Hurricane Irma highlights the urgent need to take adaptive measures in preparation for future tropical cyclones, which have been predicted to intensify as the climate warms (IPCC, 2013). The need is most pressing for island nations and territories within range of common Atlantic hurricane tracks in the Caribbean; these communities are already suffering from lack of infrastructure, laws, and funding to address catastrophic hurricane damage like that caused by Irma. Following Irma, Cuba set out to develop adaptive measures for present and future hurricanes through a program called Tarea Vida, or Project Life, led by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Environment (CITMA). The program plans to prevent new homes from being developed in threatened coastal areas, require the relocation of residents in areas doomed to sea level rise, shift crop production away from saltwater-contaminated areas, and restore degraded habitat such as mangroves and reefs (Stone, 2018). In a proposal for the plan, Cuba asks for funding from the Global Climate Fund, an international financing mechanism set up under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. While the immediate risks from tropical cyclones are most evident among islands along the common path of destruction by hurricanes, such as Cuba, coastal communities on the mainland U.S. are also at risk. For example, damages to the U.S. from Hurricanes Harvey and Irma alone are expected to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars (NOAA, 2017). References Cangialosi, J.P., Latto, A.S., Berg, R. (2018). National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Irma (AL112017). National Hurricane Center. https://www-nhc-noaa-gov.uri.idm.oclc.org/data/tcr/AL112017_Irma.pdf. IPCC (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. In T.F. Stocker, et al. (Eds.), Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1535 pp.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. NOAA (2017). Billion dollar weather and climate disasters. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/. Stone, R. (2018). Cuba’s 100-year plan for climate change. Science, 359, 144-145. |