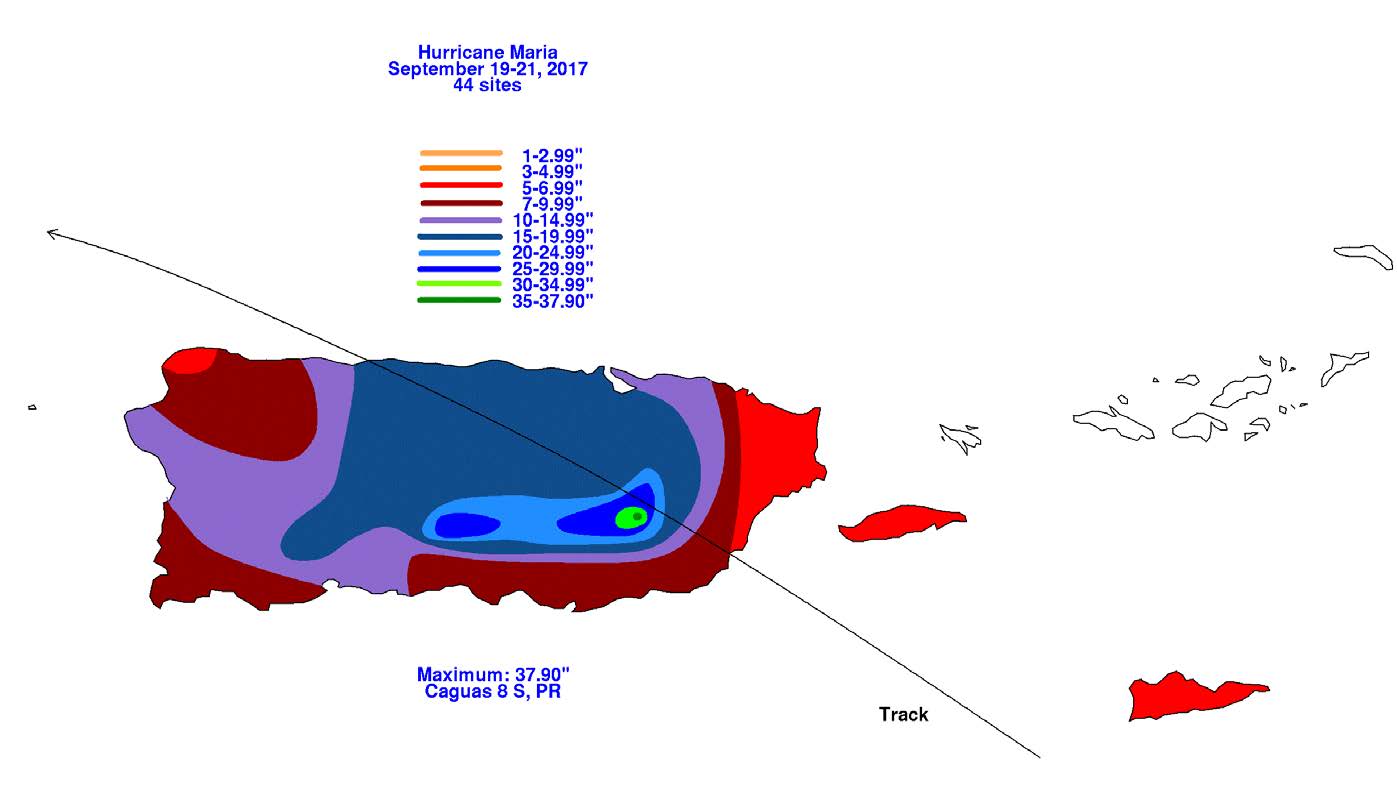

Introduction Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico as a powerful category 4 hurricane on September 20 with winds over 100 mph, and more than 30 inches of rain fell. A year later, the full extent of the damage in Puerto Rico has still not been determined, however one study determined that 2,975 deaths can be directly attributed to Maria.

Hurricane Maria was a major tropical cyclone that reached category 5 intensity. It made landfall in Dominica on September 18 as a category 5 storm and in Puerto Rico as a category 4 hurricane on September 20 with winds over 100 mph. The storm caused devastating damage to both islands. Maria hit the Caribbean two weeks after the region was ravaged by Hurricane Irma and led to widespread loss of access to roads, healthcare, electrical power, cellular communication, and clean drinking water, causing a major humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico. A great deal of flooding occurred due to the more than 30 inches of rain that fell. It was the third costliest hurricane in U.S. history, behind Katrina (2005) and Harvey (2017). While the official death count from Maria was 64, a Harvard study published on May 29, 2018 estimated the number of deaths to be around 4,645 (95% confidence interval, 793 to 8,498). Meteorology and Forecasting

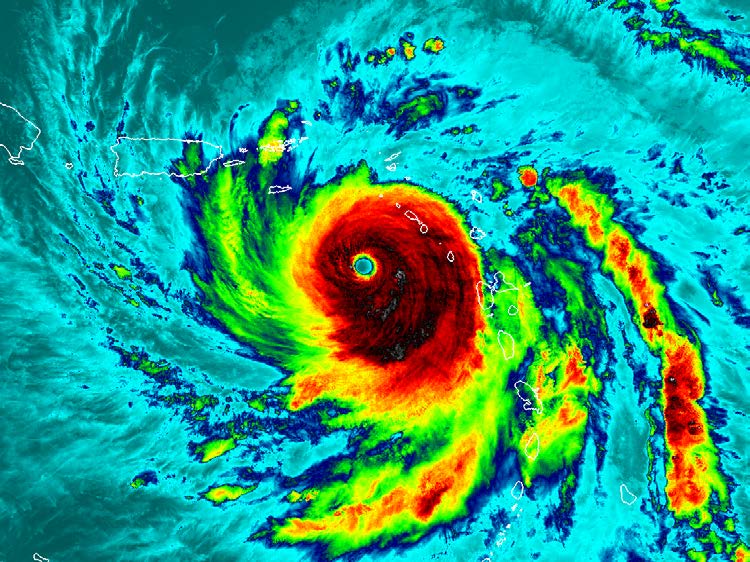

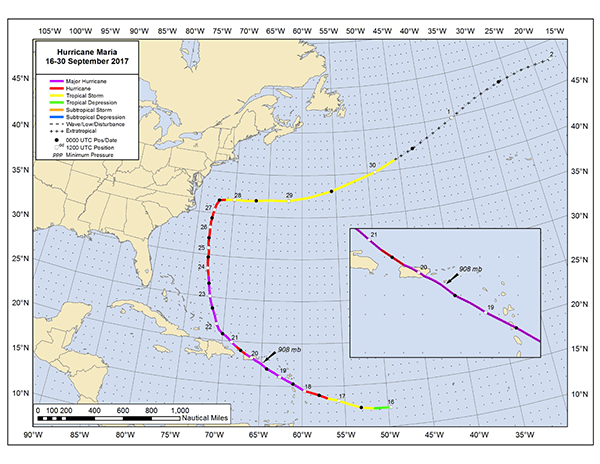

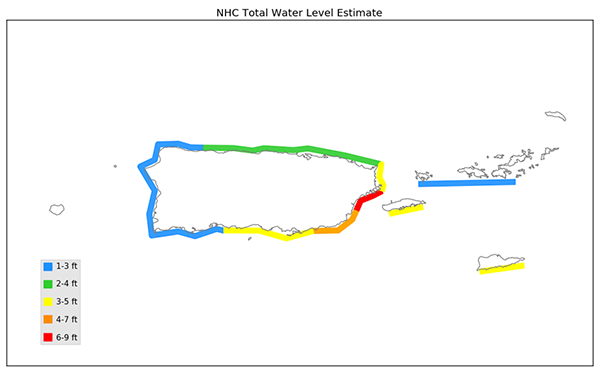

Description: On September 12th, 2017, a tropical atmospheric wave originated off the west coast of Africa, moving westward in a disorganized fashion over the tropics for a few days. By September 16th, the disturbance had become more organized and formed a tropical depression, strengthening into a tropical storm several hours later. On September 17th, the storm rapidly intensified into a hurricane due to very warm sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and light wind shear. It became a major hurricane the next day, and twelve hours later intensified into a category 5 storm as it ripped towards Dominica. The storm’s intensity fluctuated after interacting with the mountains of Dominica, but maintained category 4 intensity as it made landfall over Puerto Rico on September 20th. By September 22nd, Maria had veered northward, and for several days traveled north-northeast well offshore of the U.S. east coast while weakening, causing mild storm surge, primarily in North Carolina. By September 30th, the tropical cyclone had transformed into an extratropical cyclone, and dissipated near Ireland by October 2nd.

Intensity: Category 5 (Saffir-Simpson Scale)

Damage (estimated in 2018)

Storm tide:/b> Cost:

Adaptation (What was learned)

The effects of Hurricane Maria were a source of concern well into 2018 and the start of the new hurricane season. Puerto Rico’s infrastructure and economy were struggling before Maria, which, together with the destruction wrought by Hurricane Irma two weeks earlier, exacerbated its effects on the population. The struggle to quickly rebuild in the aftermath of the storm left Puerto Rico vulnerable to power outages. Many properties, including health care facilities, were still relying on generators for electricity well into 2018. While the Stafford Act requires that U.S. power grids and infrastructure be rebuilt in the same form as they were before the storm, grassroots movements called for solar microgrids, self-contained power derived from renewables like solar and wind power, that would keep running when large-scale power grids have failed. Microgrids are well-established in island nations like Cuba, and have helped avoid massive power outages during major hurricanes. Puerto Rico’s debt before the storm prevented money from being spent on strengthening its infrastructure and power grid, which worsened the effects of Maria’s destruction. The challenges that Puerto Rico faced after Maria exemplify the importance of adaptive approaches not only for infrastructure and power grids, but also for economic and healthcare systems in planning and preparing for natural disasters. References

Akpan, N. (2018). Puerto Rico went dark 6 months ago. Could a solar smart grid prevent the next energy disaster? PBS NewsHour. Mar 20, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/puerto-rico-went-dark-6-months-ago-heres-how-solar-energy-may-speed-the-recovery. Alcorn, T. (2017). Puerto Rico’s health system after Hurricane Maria. The Lancet. Oct 7, 2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32591-6. Holmes, R.C. (2018). Puerto Rico’s recovery, 7 months after Hurricane Maria. PBS NewsHour. Apr 19, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/puerto-ricos-recovery-7-months-after-hurricane-maria. Kishore, N., Marques, D., Mahmud, A., Kiang, M.V., Rodriguez, I., Fuller, A., Ebner, P., Sorenson, C., Racy, F., Lemery, J. Maas, L., Leaning, J., Irizarry, R., Balsari, S., Buckee, C.O. (2018). Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. The New England Journal of Medicine. May 29, 2018. Massachusetts Medical Society. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972. Pannell, I., Taguchi, E., and Louszko, A. (2017). ‘It’s all gone’: Hurricane-ravaged Dominica, on the front line of climate change, fighting to survive. ABC News. Oct 18, 2017. https://abcnews.go.com/International/hurricane-ravaged-dominica-front-line-climate-change-fighting/story?id=50559156. Pasch, R.J., Penny, A.B., Berg, R. (2018). National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (AL152017). National Hurricane Center. https://www-nhc-noaa-gov.uri.idm.oclc.org/data/tcr/AL152017_Maria.pdf. Sullivan, L. (2018). How Puerto Rico’s Debt Created a Perfect Storm Before the Storm. NPR. May 2, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/05/02/607032585/how-puerto-ricos-debt-created-a-perfect-storm-before-the-storm. Trenberth, K.E., Cheng, L., Jacobs, P., Zhang, Y., & Fasullo, J. (2018). Hurricane Harvey Links to Ocean Heat Content and Climate Change Adaptation. Earth’s Future, 6. doi: 10.1029/2018EF000825. Zorilla, C.D. (2017). The View from Puerto Rico - Hurricane Maria and Its Aftermath. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 1801-1803. Nov 9, 2017. Massachusetts Medical Society. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1713196. |