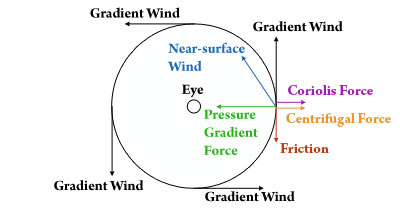

In the lower troposphere (near the earth’s surface), winds spiral towards the center of a hurricane in a counterclockwise direction in the Northern Hemisphere and in a clockwise direction in the Southern Hemisphere. Since the United States (and the rest of North America) is in the Northern Hemisphere, all hurricanes that can affect the United States rotate counterclockwise. These rotating winds are called the hurricane’s primary circulation. These winds decrease gradually with height, and near the top of the storm, the circulation reverses direction and becomes clockwise. A hurricane’s primary circulation involves four main forces: the pressure gradient force, the Coriolis force, the centrifugal force, and friction. The pressure gradient force always tries to move air from areas of higher pressure to areas of lower pressure. Since the center (eye) of a hurricane contains the lowest atmospheric pressure found in the storm, the pressure gradient force tries to pull air towards the center of the hurricane. In the Northern Hemisphere, air that is being pulled towards the center of the hurricane is deflected towards the right because of the Coriolis force, which is a result of the Earth’s own rotation. The greater the speed of the hurricane’s rotation is, the greater the strength of the Coriolis force is. With all of this inward-moving air turning to the right, the primary circulation around a hurricane begins to develop. The Coriolis force itself, however, is not strong enough to balance the pressure gradient force in a mature hurricane. An additional force, the centrifugal force, always acts outward from a rotating object. If you have ever been on a merry-go-round, then you have experienced centrifugal force. As the merry-go-round rotates faster, you may feel the need to hold on tight so that you do not get thrown off of it. The greater the speed of rotation is, the greater the outward centrifugal force is. Near the Earth’s surface, friction between the air and the surface causes the air to move slower than it would otherwise. Since the air is slower very close to the Earth’s surface, the strength of the Coriolis and centrifugal forces is less than it is above the surface, but the pressure gradient force remains strong near the surface. As a result, air spirals towards the center of the hurricane in the lower troposphere. The inward component of the moving air is part of the hurricane’s secondary circulation. |